|

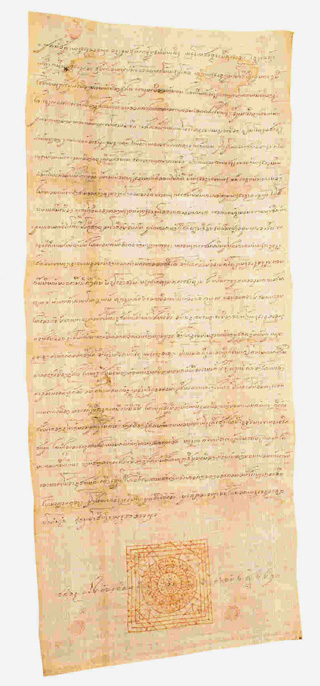

A Bai Cum sent from the King of the Vientiane Kingdom to the Lord of Xam Tai

(present Xam Tai district, Huaphan province) in 1742

[Source: Phimphan Phaibounvangcaroen, 2000, Bai Cum: Saranitaet Bon Singtho, National Library, Fine Arts Department, Bangkok] |

|

|

|

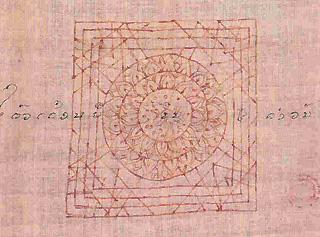

The lower part of the Bai Cum shown above (The Bai Cum was written on cloth, and the seal of the sender [the king of the Vientiane kingdom in this case] was drawn at the bottom of the cloth)

[Source: op. cit.] |

The title of my individual research is “What does the 'territory' mentioned in the administrative documents (Bai Cum) of the LanXangKingdom (Laos) refer to? Local administration and the notion of space in pre-modern mainland Southeast Asia.” It aims to clarify the actual conditions of the local administrative system in the late Lan Xang Kingdom and, through an examination of the meaning of the “territory” of each local principality, as mentioned in the administrative documents (hereinafter “Bai Cum”) of the kingdom, to elucidate the fact that before the introduction of modern Western geography into the region, a secular (material) notion of space already existed, which was generated from the necessity of local administration. This notion held great importance for the ruling people and for the securing of natural resources, and was different from the religious (spiritual) notion of space based on Buddhist cosmology.

I published An Economic History of the Lao Lan Xang Kingdom during the Fourteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (in Thai) in 2003, on the basis of the results of a research project supported by the Toyota Foundation, Japan, in FY1998, entitled “A Study on the Economic Distribution System Supporting the Growth of the Lao Lan Xang Kingdom during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, with Special Reference to the Economic Role of the Kha (an aboriginal people with a language related to Mon and Khmer).” Since then, however, I have encountered difficulties in studying the history of Laos during the mid seventeenth century and the mid nineteenth century due to the serious limitation of historical documents. About six months ago, I was informed that 22 copies of Bai Cum in the possession of the National Library of Thailand had been transliterated and published by the library in 2000. On the other hand, through an investigation of previous researches about the Bai Cum, I discovered a single master’s thesis (Silapakorn University, Thailand), which carefully examines 49 copies of Bai Cum in the possession of the library in order to clarify changes in the shapes and orthography of old-type Lao characters. Although this thesis does not deal with the historical aspect, it includes in its appendix a transliteration of the 49 copies of Bai Cum studied in the thesis. Therefore, under the present conditions, where it is not possible to freely read the original texts of the Bai Cum in the possession of the National Library of Thailand, the thesis is greatly helpful, together with the National Library version mentioned above, to researchers in deciphering and analyzing Bai Cum. According to the two books, there are 69 copies of Bai Cum from years ranging from 1600 to 1886 kept in the National Library of Thailand. They were brought to Bangkok by Siamese troops dispatched to northern Laos to conquer the Chinese Ho bandits who invaded northern Laos from southern China in the 1880s. Bai Cum generally consist of “orders” sent from the central government of the Lan Xang Kingdom* to local lords and “reports” from local lords to the central government. In particular, among the orders sent to local lords in the name of the king, we find many dealing with the appointment of a lord, the territory of a local principality, ruling people, the payment of a tribute to the king, specific products of local principalities,and so on. It is expected that an examination of these articles may partly reveal the local administrative system of the kingdom. Moreover, the fact that the king demarcated the “territory” of each local principalityin great detail leads to the hypothesis that before the introduction of modern Western geography into the region, a secular (material) notion of space already existed, which was generated from the necessity of local administration. This notion held great importance to the ruling people and for the securing of natural resources, and was different from the religious (spiritual) notion of space based on Buddhist cosmology, which led to the formulation of this research plan.

At present, I am reading the 49 copies of Bai Cum included in the two books mentioned above and examining their contents. In the next issue, I plan to explain the contents in concrete terms.

*At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the LanXangKingdom was divided into three kingdoms, namely, LuangPhabangKingdom, VientianeKingdom and ChampasakKingdom. From this period onwards, the Bai Cum were sent back and forth between the LuangPhabangKingdom and its domains, and between the VientianeKingdom and its domains, respectively. |

Report

Report