| Period: 11 - 16 March 2005. Country: Burma |

| |

Aim of Trip |

| |

Field Observation for Preparation of Comparative Research on Regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia |

| |

TANABE Akio (Institute for Research in Humanities) |

| |

Record of Activities (record place of visit, activities, dates) |

| |

3/11 (Fri) |

|

Met up with the other members at Yangon. |

| |

3/12 (Sat) |

|

Yangon - Bagan. Visited Bagan Buddhist remains. |

| |

3/13 (Sun) |

|

Bagan - Mandalay. Conducted fieldwork in a village on the way and visited MountPopa, the sacred site of Nat worship. |

| |

3/14 (Mon) |

|

Left for Yangon - Irrawaddy Delta region. Conducted fieldwork in two villages. |

| |

3/15 (Tue) |

|

Listened to reports by Japanese and Burmese scholars conducting collaborative research at the Yangon Field Station and presented comments as a discussant at Yangon University. Finished work in the evening.. |

| |

3/16 (Wed) |

|

Returned to Japan. |

| |

Research Results and Progress |

| |

- <Introduction>

- I traveled to Burma this time as part of a comparative research project. My fields of specialization are anthropology and South Asian area studies. This trip was stimulating in that it afforded me the opportunity to observe a region outside my specialization. Below I give a rather fragmentary account of my experiences during the trip.

Burma is called ‘Brahma Desh’ (the country of Brahma) in India. The name Burma or Myanmar is also said to come from the word Brahma (when I asked a Burmese to pronounce the name of their country, it sounded like ‘Byama’ or ‘Byanmar’). The region is very close to India from a traditional geographical viewpoint and formed a part of the British Indian Empire (1886-1937), so I also felt close to Burma as a researcher of India. Upon visiting, however, I realized that Burma is rather different from Indian society, though it indeed has deep cultural connections with the Indic world.

- <Social Structure and Technique of Interpersonal Relations>

- I arrived at Yangon airport on the night of 11 March and met up with Prof. Kozo Hiramatsu (Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University). Immigration at the airport influences one’s first impression of a country. The first thing that surprised me was that almost all of the immigration officers were young women. I am not good at guessing a woman’s age, but most of them seemed to be in their mid-20s. I was further taken aback by their friendliness and good manners. They always had a charming smile on their faces and even looked a little shy. When one of these officials took a passport, she would put her left hand on her right elbow or upper arm and take the passport with her right hand. Then she whispered something to the other female officers, stamped the passport and returned it with the right hand, again putting left hand below right elbow. I felt I was observing some kind of strange ritual. The experience at immigration was a shock for me, since my only knowledge of present-day Burma was based on information gained from flipping through newspapers: that the country is ruled by a military dictatorship.

In Indian immigration, the officers place (or rather throw) the passports on the counter (the fact that they do not give them by hand is related to the idea of purity/impurity). The officers are usually bureaucratic and unfriendly middle-aged men who may still become as warm as old friends suddenly if you talk to them a little. This is pleasant for those who like India, but some people might find it overly friendly or pushy. The protocol of politeness that is observing the distance between personal spaces is not found in India except among the elite. This might be related to the fact that in India social relationship norms developed according to caste status, and techniques of interpersonal relationships in public which do not question status are generally underdeveloped. In contrast, development of techniques of amity in Burma (which are not merely a formality but are actually pleasant in practice) might be related to the fact that this society has a relatively fluid social structure and is based on construction of relationships through networks.

- <Tea and Public Hygiene>

- I met up with Dr. Kazuo Ando (Center for Southeast Asian Studies, KyotoUniversity) and Dr. Nobuhiro Onishi (Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, KyotoUniversity) at the hotel. By chance, I also met there Dr. Yoko Hayami (Center for Southeast Asian Studies, KyotoUniversity) and Dr. Yukino Ochiai (ResearchMuseum, KagoshimaUniversity). We had a meal in a restaurant and chatted. When I was about to order a bottle of mineral water, Ando-san said that tea would be served for free. I was again taken by surprise. Later I learned that tea was free not only in the hotel but also in ordinary restaurants. In India, it is common sense that one needs to spend money (or effort) to get safe drinking water. I was impressed that this country is so well off that it can provide free tea. I remembered Alan Macfarlane’s argument that the average life-span of the British was extended after people started drinking boiled tea instead of only water. Serving tea instead of water is ideal from the point of view of public hygiene.

This is also related to the type of tea and the method of brewing. It is impossible to drink black tea (made not from leaf tea but from the CTC [cut, tear and curl] process, this is made from a powder that brews even in small amounts) with a lot of sugar and milk in place of water. The tea served in Burmese restaurants was the lightly fermented Chinese type with a fresh taste, which could be drunk in quantity to replenish water in the body.

- <Stroking a Child’s Head and the Culture of Care>

- On 12 March, we got up at 4:30 a.m. and left the hotel at 5:00 a.m. to catch the flight to Bagan. We met up with Prof. Min Thein. Prof. Min Thein is a professor of history at Yangon University. Calm and cool at first, he always smiled when talking to people and proved a gentleman who took great care of us. When he was boarding the plane, he helped a boy who was standing in front of him and stroked his head, smiling. I was impressed that everyone was kind to other people’s children in Burma. On another occasion, I saw someone else replace a child’s hat, again stroking his head.

In India, it is unthinkable to stroke the head of an unknown child. There is a taboo on touching, and unless a superior (in terms of age, caste or master-disciple relationship) is blessing an inferior, there is no way that a person will touch someone else’s head (even a blessing is usually given by putting the hand above the head). Conversely, it is customary there for an inferior to touch the feet of the superior in greeting.

It seems that the culture of interpersonal care in social relationships is very developed in Burma. I heard that human rights are restricted under the military regime, so I assumed that the general atmosphere would be a lot more tense. But daily social interaction was very pleasant (which of course does not mean that restrictions on political rights should be overlooked). Here it seemed that interpersonal relationships were based not on hierarchical norms or individual rights but on mutual care.

I was asked to show my ticket when boarding the bus to reach the plane, but I could not find it. As I was struggling to look for it, the person in charge smiled wryly and with a gesture let me pass, which I thought was very generous of him. Perhaps this is due to the social custom of placing more importance on interpersonal relationships rather than norms.

- <Buddhist Remains and the Bay of Bengal>

- Fortunately the weather was clear and we could see the scenery below from the plane. Ando-san brought out a map and explained to us about the geography and subsistence agriculture in the area. It was very interesting to hear explanations from someone from another discipline and I learned a great deal. The wet delta area was more limited than I imagined, and I did not expect such a widespread area of dry land. It goes to show that one must actually see a place to find out what it is like.

We visited many Buddhist remains in Bagan. There are many Buddhist remains in India too. However, I was surprised by two things in the Buddhist remains at Bagan. One was the fact that such a large-scale temple complex was built in a dry area. In India, temple complexes are usually built in wet areas where agricultural production per square area is high. Since the same is true in Java and Cambodia, I thought that this also applied to other places. But Bagan seemed to be a special case. I asked Prof. Min Thein how it was possible to maintain a temple complex of this scale, and he said that there were several theories but no definite explanation. I was also surprised that many different styles of temple architecture coexisted. I was stunned to see a temple in the Orissan style of Eastern India with a tall tower, but of course this was due to my ignorance. The styles probably differ according to the period, but the fact that there is so much variety in styles seems to be due to the fact that Burma incorporated many cultural elements from outside apart from the local cultural styles that developed relatively autonomously. In particular, the cultural interaction through trade in the Bay of Bengal was important. Prof. Min Thein later pointed out relevant sections of The Making of South East Asia by Cedes in which there is reference to the strong historical relationship between Orissa and Burma. Pegu was apparently called Usa (a corrupted version of Orissa) and there was a place called Srikshetra (another name for Puri, Orissa) in the kingdom of Pyu.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tea and snacks (free of charge!)

|

|

Bagan temples |

|

At Bagan |

| |

- <‘Tradition’ turned into Tourism and the Quality of Life>

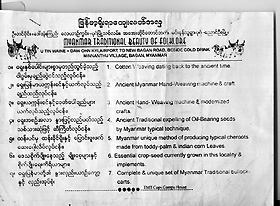

- On 13 March, we first visited a village near Bagan (Minnanthu). We went there for Ando-san’s research on agricultural technology, but it was interesting that those who agreed to be interviewed were running shops that sold ‘Myanmar traditional beauty of folklore’. They had pamphlets (see photograph 1), and displayed the process of growing cotton nearby, making cotton thread, dying the thread and weaving it into cloth. Colorful shirts and scarves were on sale just next to the display. When I asked, ‘Are these all made here?’ I was answered frankly, ‘80% is made in other factories’. They also had an oil-pressing machine with a wheel used to make sesame oil using oxen, and they demonstrated how it was used. This oil was expensive and could not be sold in the market, so most of it was consumed at home. When I asked whether it was sold to tourists, the workers asked, ‘Do you want some?’ and seemed ready to put it in a bottle, so I had to quickly stop her. This machine seemed like a display to attract tourists rather than to press oil for any practical purpose.

When I asked Ms. Tin Swe Myint (in her late thirties), who seemed to be in charge, why she started such a shop, she said that she wanted to show people tradition. We came across such shops which sold ‘traditional culture’ in other places on the way. These can be said to be typical examples of objectification of or commodification of tradition. However, I was impressed that as the people objectified, displayed and commodified tradition, they were also enjoying practice of this tradition as part of their life and clearly enjoyed sharing it with people.

Let me give an example: When some foreign tourists (I later found out that they were German) came while we were talking to Ms. Tin Swe Myint, she got out a handmade cigar and started to smoke it in front of them. The cigars were on sale, so she was giving a demonstration. Just as expected, the Germans took an interest and asked about the cigar (though they did not buy any in the end). What was interesting was that when the tourists left, Ms. Tin Swe Myint gave the cigar she was smoking to an old woman who was sitting relaxed nearby. The old woman enjoyed the cigar thoroughly. Smoking cigars here was not only a part of business but also a part of enjoying life. In more academic terms, economic activities here were not ‘alienated’ from their personhood and life.

This was completely different from the ‘tribal dance’ performances in high class hotels at dinner time, which were also an example of commodification of tradition. ‘Tribal dance’ is sold as alienated labor (of course, I cannot say that the performers do not enjoy dancing at all). However, when Ms. Tin Swe Myint and others weave cloth, make cigars, press sesame oil, sell their wares and also use them for their own consumption in their village, ‘tradition’ is by no means only a tool for making money or dissociated from everyday living. Traditional culture is lived in practice as well as used as commodity to be sold. I was impressed by this broadminded stance which compromised with capitalism when necessary, and at the same time enabled the people to enjoy a down-to-earth lifestyle. This was surely based on the people’s developed sense of balance by which they try to improve the quality of life as a whole.

|

|

|

|

| Photograph 1

|

|

Ms. Tin Swe Myint at her shop showing how to spin thread out of cotton flower |

| |

- <Pacifying Spirits and Conquest>

- We left Bagan and went to MountPopa which was a sacred place for Nat (spirit) worship. 37 Nats are worshipped at the foot of MountPopa. According to Ando-san, these were kings who were conquered and killed when the king of Burma established a dynasty in Bagan. Half of them were Indians and the other half Karens. There were clearly goddesses of Indian origin such as Lakshmi and Durga among the Nats being worshipped.

It is quite common in India that the spirits of the conquered become tutelary deities of a kingdom. However, in India’s case, they are usually sacrificial victims of tribal people who are closely related to the land, and outsiders (like the Indians in this case) are not worshipped. Takeshi Umehara has a bold hypothesis regarding the pacification of the spirits of victims of the state. He says that Horyuji was also built to pacify the spirit of Prince Shotoku. I reflected that the theme of pacification of spirit and political rule was an important one for comparative area studies. It is surely necessary to analyze this theme academically when we think about the problem of the Yasukuni shrine. This is by no means a problem unique to Japan.

Since we had come all this way, we climbed up MountPopa. There was a fresh wind and a fantastic view of the hills and paddy fields. I didn’t feel like thinking about resentment and power. The temple had many bells which echoed with a clear sound when struck. Hiramatsu-san made recordings for his research on soundscape. It is indeed impossible to describe the experience at this place without sound. I wondered whether there was any way to record the touch of the wind.

In the car on the way to Mandalay after sunset, I chatted about various things with Hiramatsu-san and Ando-san. In Japan we do not have a chance to sit and talk even though we are so nearby. We had a good time talking about various things including our impressions of Burma, the sciences and the arts in area studies, of Okinawa, Japan, India and Southeast Asia, agricultural technology and development, the significance of sound archives, what each of us has been doing and what we plan to do in future. It was enjoyable and I gained a good deal from our conversation.

- <The Glass Palace in Mandalay>

- On the morning of 14 March, we went to the airport after seeing the palace at Mandalay from the outside. I was very impressed with Amitav Ghosh’s novel GlassPalace and wanted to see the palace at Mandalay properly, but unfortunately there was no time. In fact, I was grateful that we could go to the palace on the way to the airport at my request. GlassPalace is a historical novel on a grand temporal and spatial scale describing the downfall of the royal family of Mandalay and their life in India, the life of Indian immigrants in Southeast Asia, and anguish of Indian soldiers over whether to support the British or the Japanese during the East Asia/Pacific War. I recommend this book for those who want to learn of the interaction between South Asia and Southeast Asia during the colonial period and the influence of the Japanese on these regions, or for those who just want to enjoy a good novel. As far as we could see from the outside, the walls and moat of the palace of Mandalay were sturdily built, giving a rather practical and functional impression.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Nats (spirits)

|

|

At the summit of Mount Popa |

|

Mandalay Palace |

| |

- <The Public Sphere and Water; Dealing with Accidents>

- We took a flight from Mandalay and Yangon and visited two villages (Kyashok and Alanzi) where fieldwork was being conducted by the Yangon Field Station. What impressed me most of all was the fact that there was a water tank at the entrance of a village temple from which anyone could drink. Moreover, this drinking water tank was set up by one of the villagers. It is good for village development that villagers want to prepare public facilities in this way. The source of the water was the IrrawaddyRiver, and the water was filtered for drinking.

The establishment of a drinking water facility in a public place is difficult in Indian villages where there are strict rules of purity/impurity. Historically there have been many disputes over the use of wells in relation to movements to liberate ‘untouchables’. Today, tube wells are being dug in each hamlet by government development projects. These policies aim to increase convenience by increasing the number of water sources, but they also seem to have the hidden motive of avoiding intercaste disputes. Caste divisions in India are certainly not helpful in the development of public facilities.

On the way back to Yangon the night after visiting the villages, the car lights broke and we were literally stranded. We telephoned the travel agent in Yangon and asked for a replacement car to be sent, but we had to wait for the car to come from Yangon. We talked in the dark and just as we were so tired that we could not talk anymore, the person in charge arrived with the car from the travel agency. Whereas Ando-san tried his best to demonstrate his anger and protest, the person from the travel agency continued to smile and just kept apologizing. It may have been his particular character, but he even seemed to be just trying to laugh the trouble away. Our anger seemed to slide off him like water off a duck's back. In India, the travel agent would probably give a speech about how they were doing their best, that the accident was unavoidable (in traditional terminology, due to Karma), hint how difficult it was to come all the way here at night and present a bill for the substitute car. We would also have had to point out the fault of the travel agent logically and argue sternly. In negotiation at times of such accidents, differences in social relations and culture appear clearly.

Whereas in logic or in social relations Indians try to divide and analyze things sharply, the Burmese try to settle things amicably without analysis. This is a rather rough conclusion but this is how I perceived it then.

- <Last Day in Yangon>

- On 15 March, I listened to three research reports at YangonUniversity. The proposal for integrated area studies by Onishi-san, the paper by Dr. Daw Pyone Aye on drinking water, and the paper on modernization in villages by Dr. Win Myat Aung were all interesting and excellent presentations.

I had some time before my flight so I visited Shwedagon Pagoda. This temple is wonderful from an architectural point of view. I was further impressed by the calm and peaceful atmosphere inside the temple, which indicated the deep religious feelings of the visitors.

One thing that surprised me was that the visitors were all using the same cup to drink the sacred water from a pot and were putting their mouth on the cup. If one person had hepatitis, I couldn’t help thinking, the virus would spread immediately. As I have said above, in India, it is unthinkable for the general public to drink water from the same pot. I think the issue of open access to public resources and public health would be an interesting topic for comparative area studies.

- <Conclusion>

- Since I have written in a rather random way, I have no conclusion as such. I am sure, however, that this visit to Burma has provided a great stimulus for my research. Comparative area studies would be methodologically difficult to pursue in a strictly academic manner, but even if researchers specializing in different areas just get together for discussion, they could help each other enormously. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Ando-san who attended to us in spite of his busy schedule and Onishi-san who made arrangement.

|

|

|

|

| Drinking water facility in front of a village temple

|

|

Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon |

| |

Future Agenda |

| |

- It is necessary to discuss further the methodology of comparative area studies as well as systematically providing opportunities for joint fieldwork by researchers specializing in different fields.

|

|

|

Report

Report